The concept of certain kata being lost to the sands of time is not a new one. However, among these lost forms, none have been remembered and preserved quite like the infamous Channan kata. Even today, we remain uncertain, and it’s possible we may never truly know whether Channan was a single kata or two separate ones known as Channan-dai and Channan-sho. Additionally, the exact origins of this kata (or katas) continue to elude us. The reason behind the enduring memory of Channan can be traced back to a notable reference from as far back as 1934.

Historical accounts.

Early Written References to Channan and Pinan.

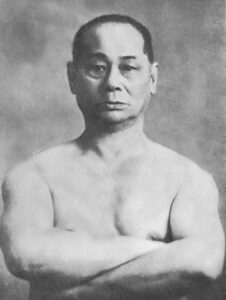

Arguably the most well-known reference to Channan kata dates back to 1934. In the karate research journal titled “Karate no Kenkyu,” published by Nakasone Genwa, Motobu Choki is quoted making mention of both Channan and the Pinan kata:

“I was interested in the martial arts since I was a child, and studied under many teachers. I studied with Itosu Sensei for 7-8 years. At first, he lived in Urasoe, then moved to Nakashima Oshima in Naha, then on to Shikina, and finally to the villa of Baron Ie. He spent his final years living near the middle school.

I visited him one day at his home near the school, where we sat talking about martial arts and current affairs. While I was there, 2-3 students also dropped by and sat talking with us. Itosu Sensei turned to the students and said “Show us a kata.” The kata that they performed was very similar to the Channan kata that I knew, but there were some differences also. Upon asking the student what the kata was, he replied “It is Pinan no Kata.” The students left shortly after that, upon which I turned to Itosu Sensei and said “I learned a kata called Channan, but the kata that those students just performed now was different. What is going on?” Itosu Sensei replied “Yes, the kata is slightly different, but the kata that you just saw is the kata that I have decided upon. The students all told me that the name Pinan is better, so I went along with the opinions of the young people.” These kata, which were developed by Itosu Sensei, underwent change even during his own lifetime.”

There is also a reference to Pinan being called Channan in its early years in the 1938 publication “Kobo Kenpo Karatedo Nyumon” by Mabuni Kenwa and Nakasone Genwa. Mabuni and Nakasone write that those people who learned this kata as Channan still taught it under that name.

Kinjo Hiroshi, a respected karate historian and a student of Itosu’s disciples, also contributed to this theory. He highlighted that the Pinan kata were originally identified as Channan. Hiroshi discerned technical disparities between Channan and the later, refined versions called Pinan, underscoring the notion that Channan served as a foundational precursor to Pinan.

Theories.

Theory 1: Anko Itosu’s Evolution of Channan into Pinan.

This theory gives Itosu all the credit for the creation of the Chanan/Pinan kata.

Anko Itosu embarked on a journey to simplify the introduction of karate in the late 19th century, resulting in the creation of the Channan kata. This kata represented a raw and unrefined version of what would later become the well-known Pinan kata. Channan drew its inspiration primarily from Kusanku. Even today, this influence is evident in all the Pinan kata.

As Itosu continued his pursuit of perfecting Channan, he realized the need for further refinement. To enhance the accessibility of karate for beginners, he took the bold step of breaking down Channan into even smaller, more digestible components. This resulted in the Pinan Series.

Theory 2: Channan as a Chinese Influence.

An alternative theory suggests that Channan, which later evolved into Pinan, may have had its roots in Chinese martial arts rather than being solely created by Anko Itosu. It posits that Itosu learned a series of Chinese Quan-fa forms, possibly from a shipwrecked Chinese martial artist in Tomari.

According to this theory, Itosu did not create Channan from scratch but rather adapted and modified the Chinese kata he learned. The source of these kata is believed to be a Chinese man named Channan (Chiang nan) or from an area called Annan.

While this theory suggests that Channan had Chinese origins, it is essential to note that the true source of Channan remains speculative due to limited historical documentation. However, it offers an intriguing perspective on the possible influence of Chinese martial arts on the development of Channan and, subsequently, Pinan.

Theory 3: Matsumura Sokon.

A final possibility is that Itosu