In recent years, traditional weapon training, known as Kobudo, has witnessed a remarkable resurgence. It has seamlessly integrated into various martial arts schools and systems, often becoming an indispensable component of Karate training.

The Classic Warrior’s Path.

Kobudo (古武道), a Japanese term directly translated as the “classic/old warrior’s way,” predominantly encompasses traditional weapon styles originating from Okinawa and classical styles from Japan.

Breaking down the meanings of each character:

- 古 (Ko): This character means “old” or “ancient.”

- 武 (Bu): This character means “warrior” or “military.”

- 道 (Do): This character means “way” or “path,” often used in the context of a philosophical or spiritual path, such as the way of martial arts.

The Arsenal of Okinawa Kobudo.

Okinawa Kobudo boasts a diverse array of weapons, including the Bo, Jo, Sai, Tonfa, Kama, Nunchaku, Eku, Tinbei/Rochin, and Tekko, among others.

Unveiling the Origins.

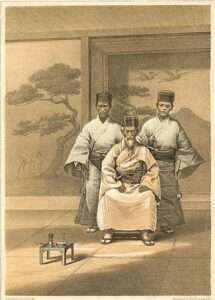

Kobudo’s development and refinement can be credited to the Okinawan upper class, known as the Pechin. In Okinawa, similar to Japan, a class system existed, and the Pechin held prominent positions. They had the time and resources to carefully develop complete combat systems.

The Pechin had diverse roles, including serving as police officers, administrators, and royal bodyguards. They even traveled to China, immersing themselves in Chinese martial arts, literature, and calligraphy. Upon their return to Okinawa, they brought back valuable knowledge, enriching their martial expertise.

Debunking a Myth: Peasant Martial Masters.

Contrary to a romanticized narrative that suggests peasants developed Kobudo and Karate to resist oppressive rulers during a weapons ban, historical research presents a different reality. It seems highly implausible that individuals engaged in farming, fishing, and similar vocations would have developed sophisticated combat systems. Moreover, the upper class had little interest in equipping commoners with techniques that could potentially threaten the government.

Nevertheless, at certain points in Okinawa’s history, a ban on carrying weapons sparked legends of farmers mastering the art of combat. Some suggest that resourceful individuals turned everyday tools, widely used by all, into techniques for both defense and battle.

Transformation of Ryukyu’s Elite: The Yukatchu’s Shift in Status.

In 1879, Japan took over the Ryukyu Islands and established Okinawa prefectures. The Yukatchu, who were the aristocratic elite of Ryukyu, lost many of their traditional privileges and status. They were no longer a distinct social class with special rights. The Ryukyuan government, once led by the Yukatchu, was dissolved, and Ryukyu became fully integrated into the Japanese administrative system. This shift had a profound impact on the economic well-being of the upper class, thanks to the introduction of land reforms that reshaped land ownership.

To adapt to these changes, some Yukatchu members took on new roles in the Japanese administration or ventured into business. In essence, Japan’s annexation of Ryukyu in 1879 brought about significant alterations in the social, cultural, and economic status of the Yukatchu, marking the end of their traditional privileged positions.

Following this annexation, some Yukatchu members may have transitioned into farming or become peasants due to changes in land ownership and economic reforms introduced during this period. This transformation may have contributed to the folklore suggesting that farmers were the inventors of Karate and Kobudo.

Prominent Schools and Diverse Traditions.

Presently, the majority of Kobudo systems can trace their lineage to three primary schools in Okinawa: Ryukyu Kobudo 1, Matayoshi Kobudo 2, and Yamanni-ryu (Yamane-ryu) Kobudo 3. In addition, numerous smaller family styles and traditions have emerged, each enriched with its unique historical background. Similar to the evolution of Karate, several organizations and directions have emerged from these main schools, all preserving the core principles of the foundational systems.

What unifies these diverse Kobudo styles is their reliance on basic techniques, kata (formal exercises), and Kumi series, mirroring the structured training seen in the world of Karate.

Seamless Integration into Okinawan Training.

Kobudo often seamlessly integrates into Okinawan training regimens. Most dojos have either incorporated Kobudo into their standard curriculum or offer specialized Kobudo classes. This integration is a natural fit as working with weapons demands a solid foundation in basic positions and a profound understanding of movements. Typically, this foundation is forged through Karate training, creating a strong connection between the two disciplines.

Several Karate masters argue that Kobudo enhances Karate, compelling practitioners to execute movements with greater fluidity, balance, acceleration, and focused power.

Kobudo, with its rich history and emphasis on traditional weapons, remains a captivating facet of martial arts, offering a unique blend of heritage and practicality. Whether pursued as an extension of Karate or as a standalone discipline, it continues to be an integral part of Okinawan martial culture.

Thanks for reading.

Gert

Footnotes.

1 Ryukyu Kobudo is the branch of Okinawan Kobudo developed and systemized by Taira Shinken under the “Ryukyu Kobudo Hozon Shinko Kai association”.

2 Matayoshi Kobudo is a general term referring to the style of Okinawan Kobudo that was developed by Matayoshi Shinpo (又吉眞豊) and Matayoshi Shinko (又吉眞光) during the twentieth century.

3 Yamanni-ryu (also Yamanni-Chinen-ryu and Yamane Ryu) is a form of Okinawan kobudō whose main weapon is the bo, a non-tapered, cylindrical staff. The smaller buki, such as sai, tunfa (or tonfa), nunchaku, and kama (weapon) are studied as secondary weapons.

Share this article